|

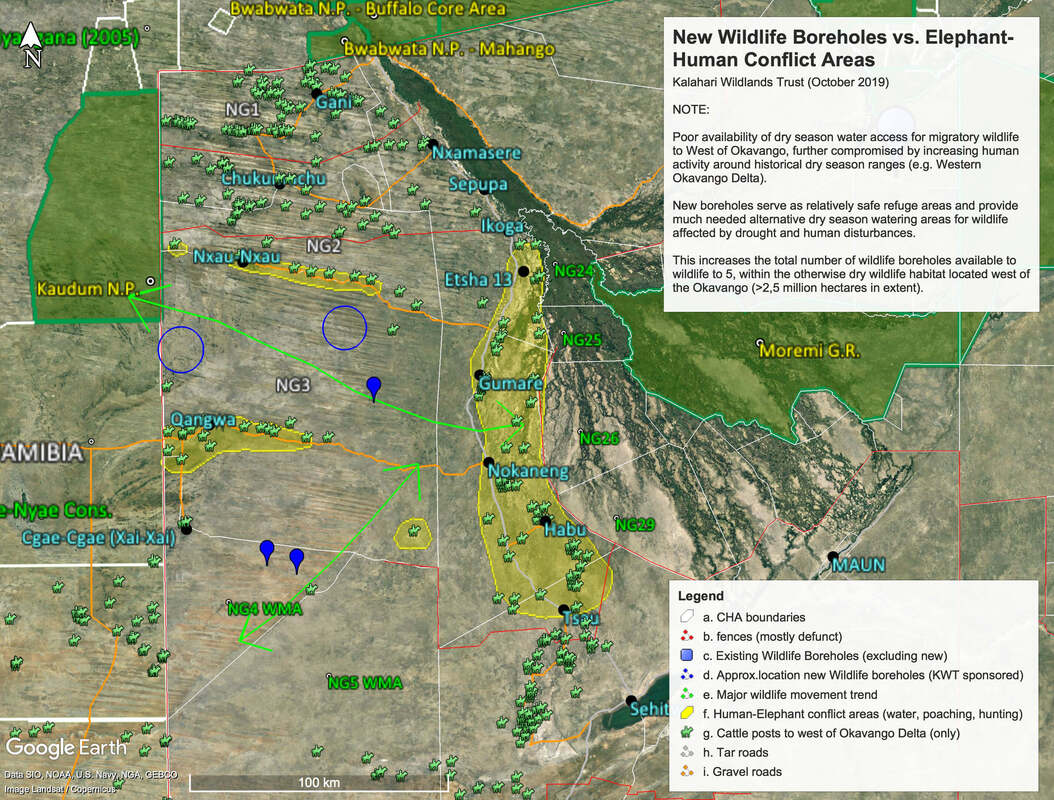

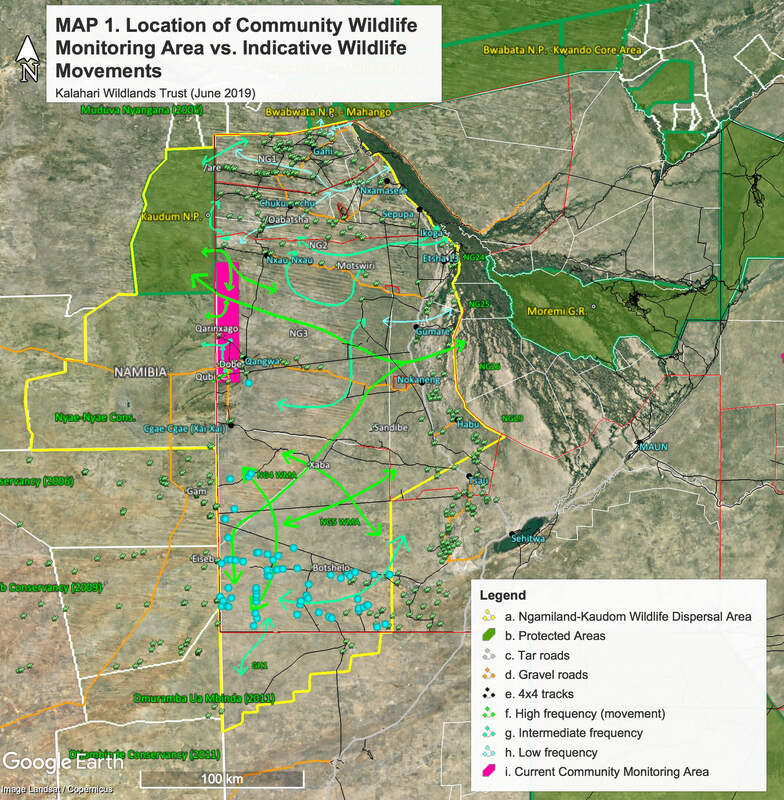

Northwestern Botswana's wildlife ecosystem is under increasing threat from human population growth, livestock overgrazing and poaching, especially around the periphery of the world-famous Okavango Delta. With the support of Oak Foundation, we have recently activated two boreholes in a remote dryland region located west of the Okavango, for exclusive use by migratory wildlife. These new solar powered water points are intended to help stabilize wildlife populations under threat from drought and the progressive loss of wildlife access to traditional dry season grazing areas, in particular along the western fringes of the Okavango (see map). Conserving and rehabilitating these migratory wildlife populations is vital to empowering local communities intent on participating in the tourism industry. Poverty eradication and the development of sustainable livelihoods is also essential to the effective conservation of wildlife and the protection of the greater globally significant wilderness landscape. If implemented conservatively, boreholes in uninhabited areas west of the Okavango, can help to stabilize and rehabilitate wildlife populations. In some instances they may also have the potential to provide focal points for the creation of community-owned campsites catering to the still-untapped self-drive adventure tourism markets (based on an unfenced land-use approach which we strongly advocate for this still largely unfragmented landscape). They can also play a valuable role in providing alternative resource areas for wildlife to help reduce regional conflicts, particularly related to elephants and predators. The Okavango Delta is but one part of a much larger regional ecosystem that must be protected, and recognition of the importance of the dryland areas to the West is finally gaining traction in conservation circles. Rehabilitating connectivity between habitats in Botswana and Namibia that were once historically linked, is key to ensuring long-term ecological resilience and unlocking the region's full tourism and sustainable wildlife use potential. Failure to conserve the ecosystem as a whole will ultimately undermine the long-term viability of the Okavango and other increasingly geographically-isolated protected areas where tourism is primarily focussed and has already reached saturation point. Growth in the tourism sector - and further employment - will not be possible without creating opportunities in these outerlying ecologically-connected areas. This requires careful and unconventional approaches to tourism development that won't undermine the more important unique selling points of the dryland areas, namely their wilderness and cultural attributes. Over the past four months we have been engaging with local communities, government agencies, solar borehole contractors, field teams and other conservation organizations in planning, equipping and monitoring two new boreholes (see map). The hard work is already paying off - a variety of mammal and bird species (many suffering acute dehydration stress) have been quick to respond to the water points and we believe this will help to reduce wildlife mortality rates in the general area. Community members have been employed to actively monitor and guard the sites and camera traps are also being used to guage wildlife responses. We would like to thank the equipment and installation contractors (Sunray Solar, Water Africa) and Ben Heermans (Habu Elephant Development Trust) and the Trustees of Morama Trust (Chris Kruger and Peter Stevens) for their project support. A special thanks is also due to Dan Kelly, Luisa Hemling, Kashe Nxauwe, Dahm Xixae and the assigned Ju/hoansi San community team members, who have all gone the extra mile, and under extremely challenging conditions, to help prepare, oversee and monitor the sites and liaise with the communities. Although much progress has been made to date, we rely on donations to continue our work. Urgent additional funding assistance (8,500 USD) is needed to help cover the ongoing costs of maintaining and monitoring these sites for at least the next 3 months. This will primarily be used cover wages, food, transportation, monitoring and resupply costs for the support crews and community team members stationed at these remote locations. Protection of the sites from poachers is also particularly important at this time. The observed climatic trend has been of increasingly erratic and late rainfall, and we do not expect local habitat conditions to improve before late January or February 2020. Above: The new Western community-owned borehole now being regularly visited by elephants, zebra, roan, gemsbok, kudu, leopard, hyena and other wildlife. The wildlife populations of this remote area are highly valued by the local Ju/haonsi San community as a tourism and culturla heritage resource, but have been in danger of decline this year due to the extreme drought conditions and resultant dehydration stress and loss of condition. Wildlife further afield and closer to human habitation are even more vulnerable due to lack of protection. Only very limited supplies of borehole water have been available in neighbouring Namibia (Nyae-nyae consrevancy) and the border fence, although broken down in places, may still be difficult for willdife to cross over. The general lack of dry season water availability for wildlife is clearly evident in the above map.

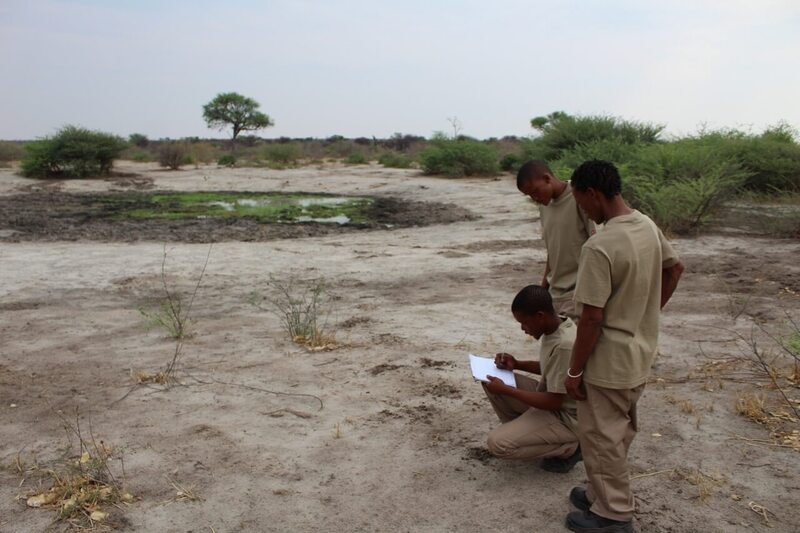

Historically, this wildlife would normally move southwards in the dry season, towards the fossil river valley where the Qangwa, Mahopa and Dobe villages are situated. Today however, those areas are heavily disturbed and severely degraded by cattle overgrazing, rendering the natural springs there severely depleted and no longer accessible to wildlife - except to some degree, elephants. This new remote water point, together with the Eastern (Morama) borehole, thus now provides relatively safe refuge and is valuable mitigation for the loss of wildlife access to southerly ancestral dry season ranges and to ranges along the Western Okavamgo delta. Zebra from as far afield as the western Okavango, 120km to the East, have also recently arrived. More elephants are expected to arrive soon from the conflict areas, on account of increasing incidents of poaching, shooting by farmers, and the recent issuing of citizen hunting licences (after an absence of hunting pressure of 10 years) - all of which are increasing stress levels in herds located there. Below: Eastern (Morama) borehole owned by Morama Trust which was last operated as a diesel-pump wildlife borehole more than 5 years ago and has now been reactivated as a solar borehole under this project. The assigned staff are tasked with regular monitoring and patrols into the surrounding area to assess wildife movements and responses to the water point. One of our objectives is to provide water to the largest remaining subpopulation of zebra still linked to the western delta (Ikoga lagoon area), which has been hard hit by the extremely low flood levels in the Delta this year and intrusion of new cattle posts in some important summer breeding ranges.

0 Comments

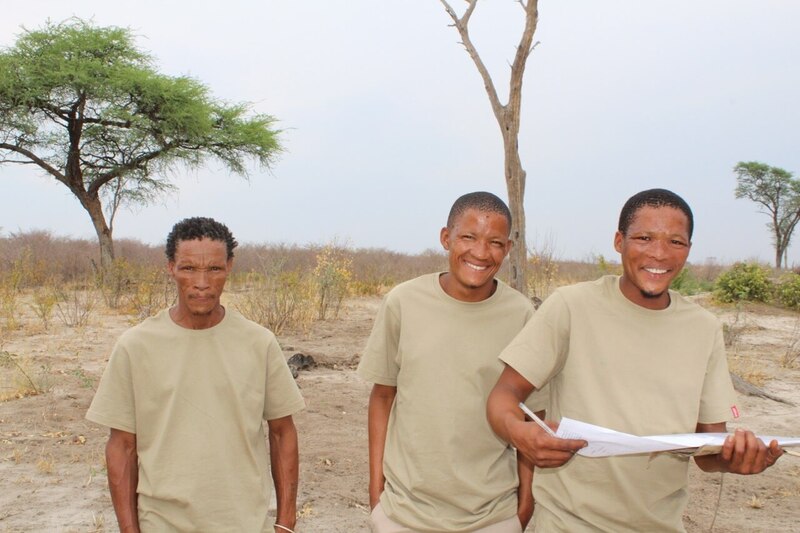

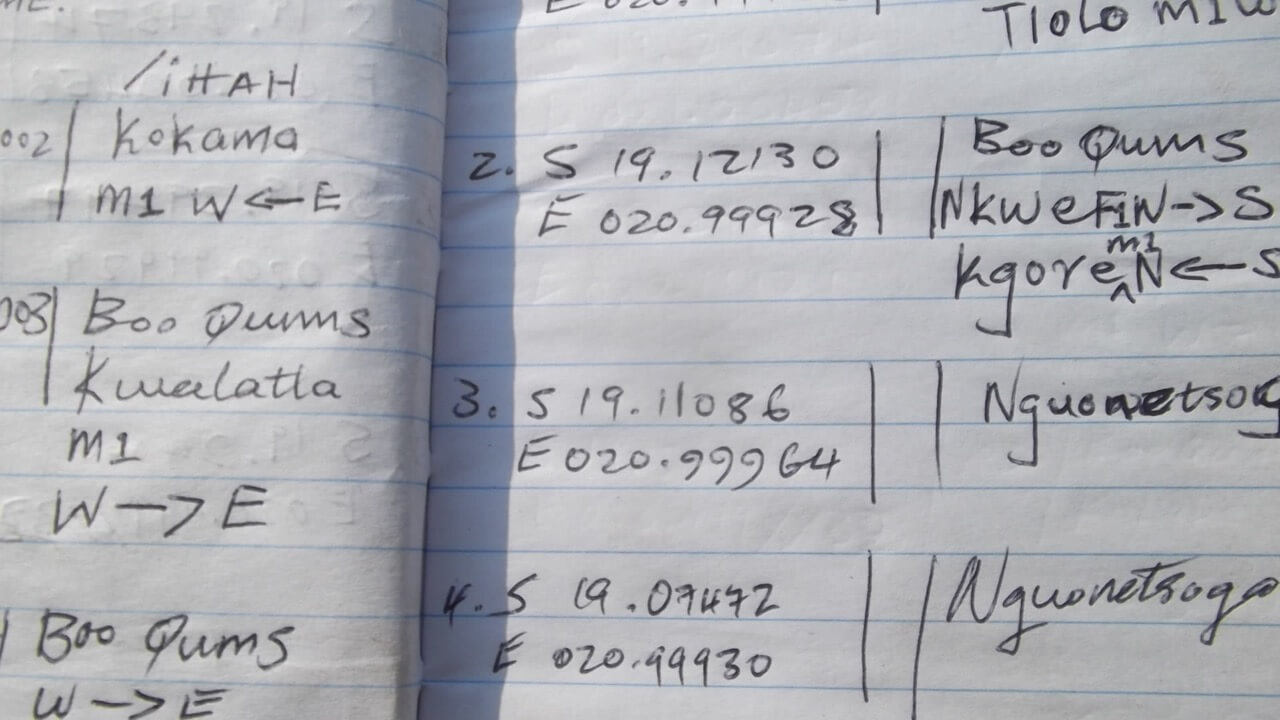

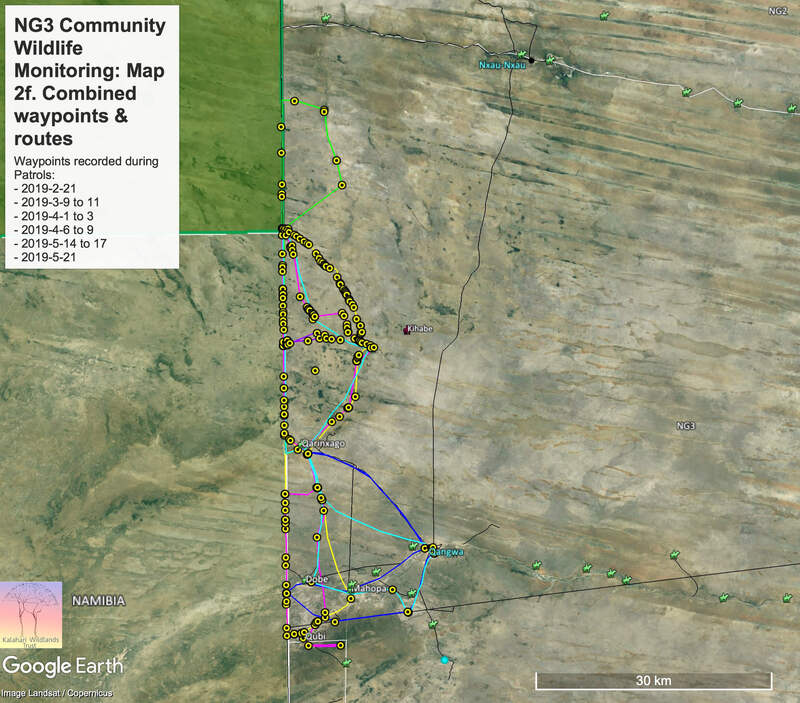

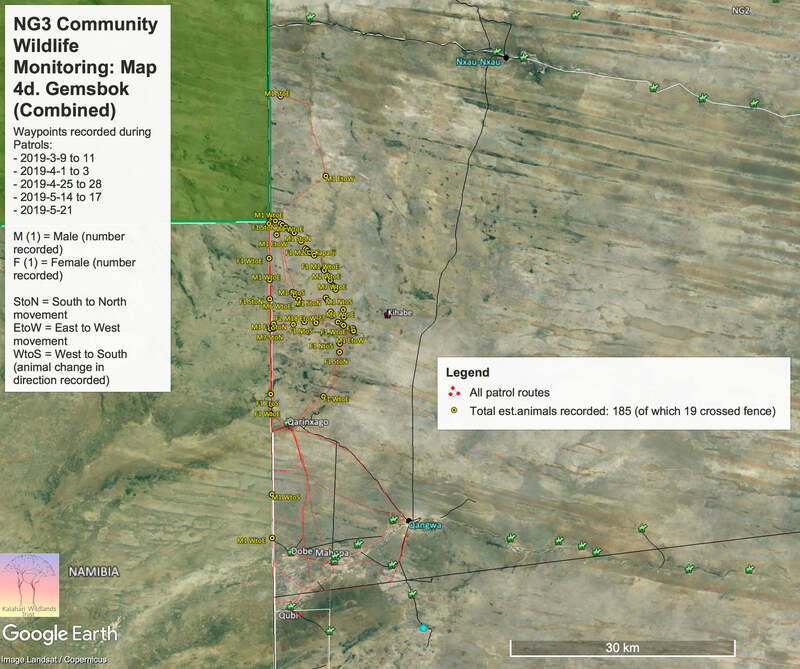

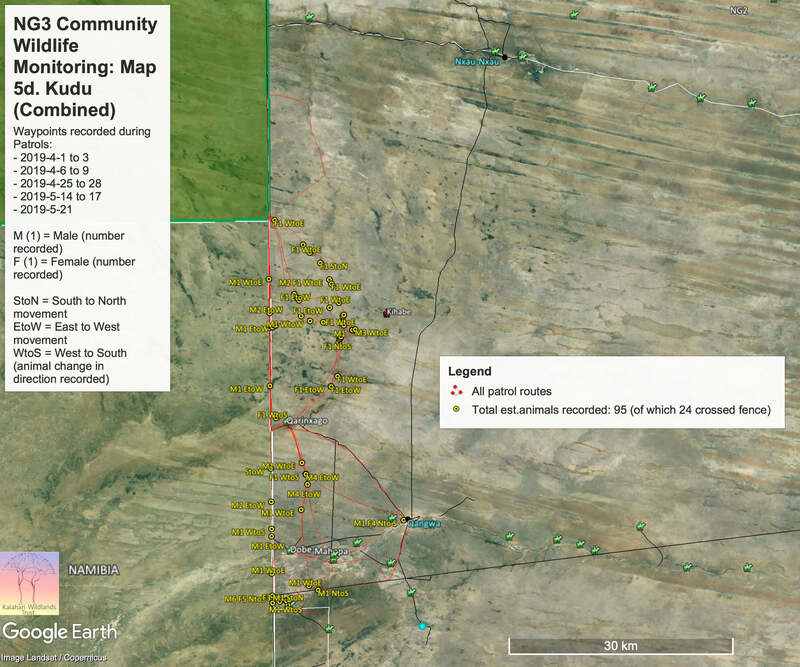

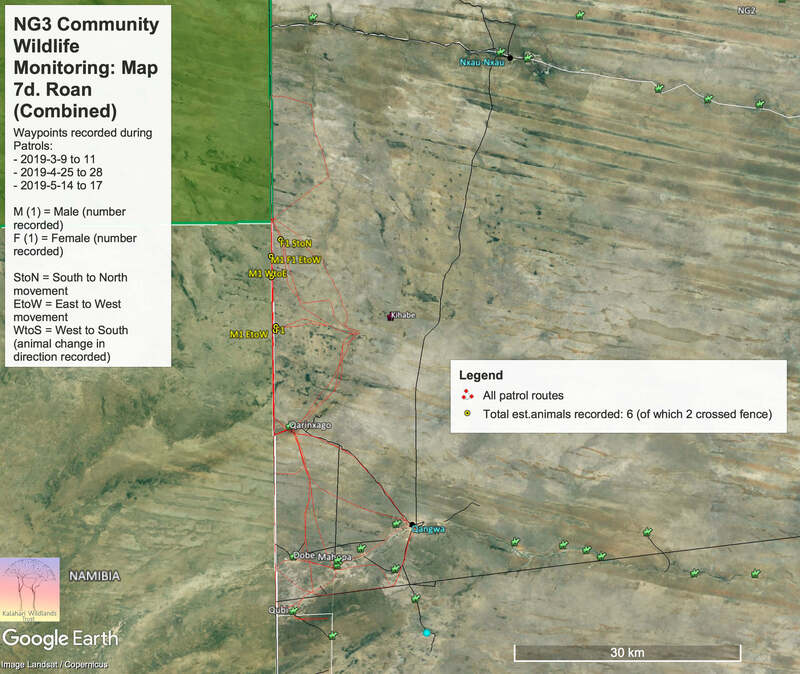

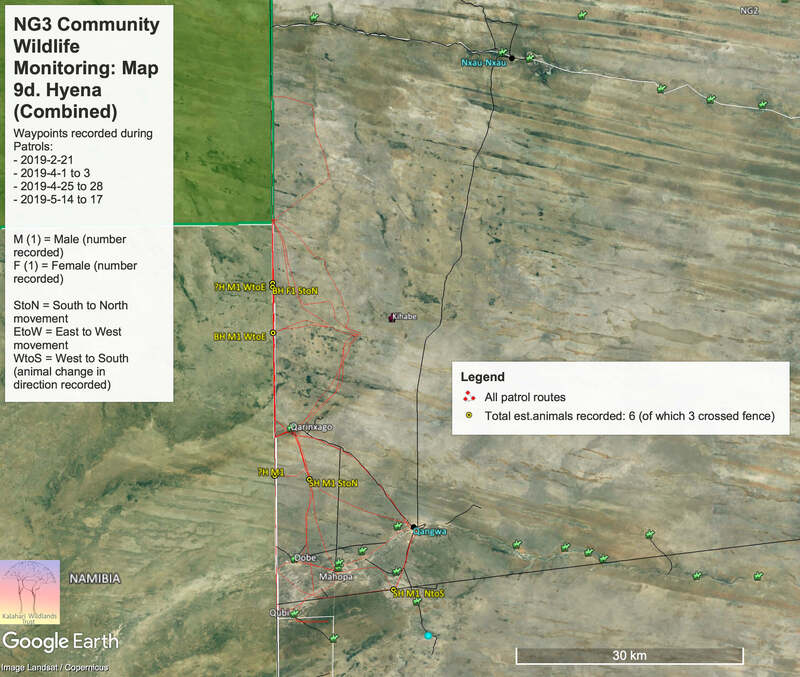

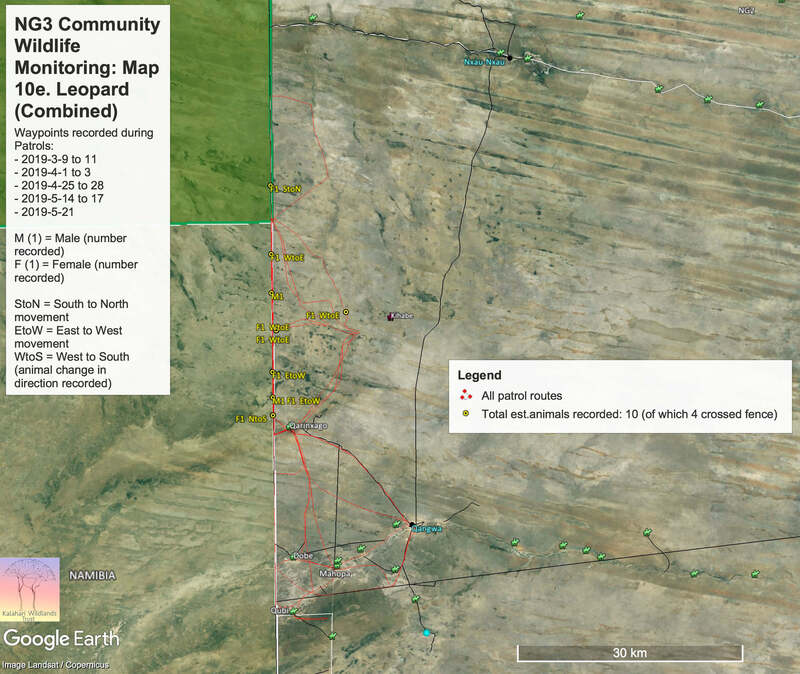

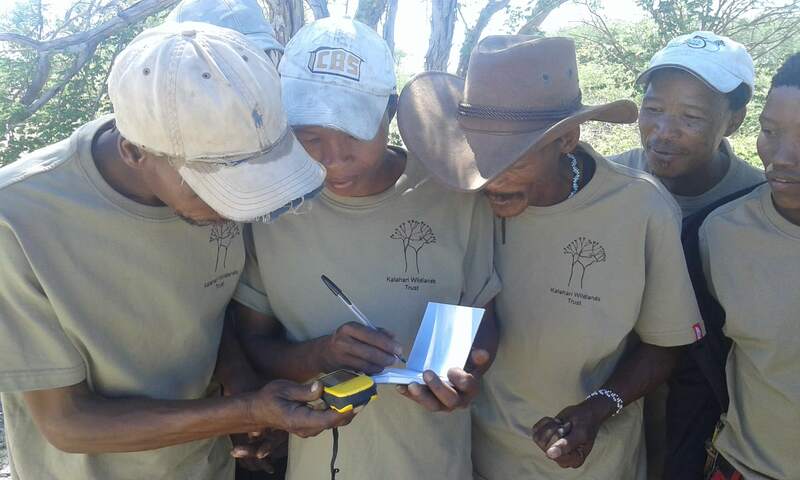

Following our earlier post in February 2019 on the training of Ju/hoansi San wildlife monitoring team members, we implemented a trial monitoring programme over a period of three months (March to May). The patrols were carried out on foot by two patrol teams, who repeatedly surveyed sections of the Namibian border-fenceline as well as adjacent habitats (See Maps below).

Under challenging conditions, the team covered more than 700km of mostly remote and uninhabited terrain, in the process obtaining valuable data on wildlife distributions and movement patterns, sex-ratios, direction of movement and movements across the decaying border fence-line. Data for all large mammals was collected, for example: elephant, eland, gemsbok, kudu, roan, wild dog, hyaena, leopard and others. The results indicate, inter-alia, that there is a high frequency of cross-border widlife movement (despite the fence still mostly being upright) and that vast areas on the Botswana side are still intact ecologically, but need improved connectivity with Namibian habitats in order for further rehabilitation of wildlife population numbers to take place via in-migration from Namibia. Predators were however found to be surprisingly low in number, and this is most likely due to a combination of wildlife poisonings over the years by farmers on the Botswna side and over-selection of males in trophy hunting oprations on the Namibian side (in the case of leopard). This is a very special initiative that the community is proud to be involved in, as they identify strongly with its purpose. They see their work here as being integral to their long-term efforts to preserve their land, cultural identity and natural resources, all of which are vital to their current and future well-being. The project has a number of valuable outputs, in that it:

The programme urgently needs funding support to enable it to continue and develop further. We need to train and include more team members, get the teams better equipped, and expand the programme to include other interested communities, thereby also expanding the extent of the border area and total wildlife habitat area under regular monitoring observation. Over the weekend of June 22nd and 23rd, we carried out emergency repairs to an ageing community solar borehole that, after 15 years of no internal maintenance, had finally failed only a few days earlier. This left a very remote San community and their animals completely without drinking water (exacerbated by the current severe drought in Botswana). With the clock ticking and both the community and their animals dehydrated and in grave danger, we managed to get the water supply going again after 4 days of no water. Whilst waiting for the installation team to arrive, we also orgnized a private water delivery of 500L to help stave off everyone's severe thirst! The old "see-saw" type pump, panels and internal rods were all removed and replaced with a completey new system incorpoarting a submersible pump, piping and cables, new panels and control box, with a complete flush done beforehand to extract loads of accumulated dirt and other contaminants at the bottom of the borehole (60m below ground) which had been affecting the quality of the water supply. We are thanful for the hard work done by Water Africa's field team, who worked well into the night to get the job done. A huge thanks to Mike and Karen McCune and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation for their funding support, which made all this possible!!

The Australian Government-spearheaded International Savanna Fire Management Initiative (ISFMI), in partnership with the Botswana Government, recently launched its Botswana pilot project, centered around two pilot sites currently experiencing a high frequency of destructive wildfires. We had the honour of facilitating, and logistically supporting, an important component of the ISFMI crew's activity schedule last month: the first-ever cultural exchange between Aboriginal Australians and Southern Africa's San (Bushmen), which took the form of a visit by Aboriginal "fire rangers" and their supervisors from the Kimberley region of Northern Australia, to the remote Ju/hoansi San community of /Oabatsha, west of Tsodilo Hills (Northwest District). Although living worlds apart, the Aboriginal people of Australia and the San of Southern Africa, are connected to one-another by virtue of their hunter-gatherer cultural origins and their traditional fire management knowledge. And interestingly, their techniques for making fire by friction are virtually identical. Indeed it is such shared ancient knowledge that is fundamental to the effectiveness of the ISFMI. The ISFMI has achieved global success in its project areas by reducing wildfire-related carbon emissions by up to 50%, thereby rehabilitating the biodiversity of the affected areas, improving food security, and creating opportunities for local employment through carbon market opportunities. Now rapidly gaining recognition as an important intervention in efforts to combat man-made climate change, the ISFMI has essentially modeled its approach to fire suppression on the ancient knowledge systems of the Aboriginal hunter-gatherer communities of Australia. For thousands of years, the Aboriginal people of Australia - just like the San of Africa - have implemented rotational early winter burning ("cool fires") between April and June. This is done to reduce combustible dry fuel loads, thereby suppressing the conditions that lead to the outbreak of large and very intense, late dry season "hot fires" (September to December). Many deciduous plants redistribute their energy reserves in the late dry season towards the exposed outer growing meristems (e.g. flower and leaf buds), which may be activated before any rains fall, thus rendering them particularly vulnerable to heat damage. The emerging trend in recent years in Northern Botswana of heat extremes coupled with delays in the start of the rainy season has exacerbated the level of damage being done to Botswana woodlands. Once also plagued by frequent, destructive wildfires, the Australian Government has only in recent years realized that conventional methods for fire suppression, centered around complete intolerance of all forms of fire, have failed dismally to bring wildfires under control. It has come to light that the revival of traditional Aboriginal burning practices, which it had outlawed decades ago following the colonization of Australia, is in fact essential to maintaining the health and vigour of savanna landscapes. These landscapes have long adapted to the presence of hunter-gatherers and their rotational land use systems and the anthropogenic effects span many thousands of years. The territorial land use systems implemented by the hunter-gatherers also included the use of fire to maintain the diversity and productivity of the biotic components on which their survival ultimately depended. In a similar sense, the ISFMI project will also be reviving the traditional knowledge systems of the San as a key strategy in guiding burning programmes that will reduce the frequency of the intense, destructive fires that have become common-place. It represents a vital opportuntity to start reversing many years of progressivley accumulating environmental damage, characterised widespread loss of tree cover, decline in spevies richness, and deterioration in the wild plant food supplies on which the San and others still depend for their health and well-being. Over the past two weeks we successfully implemented phase 1 of our endeavour to provide Botswana's remotest communities - the hunter-gatherer San and Bakgalagadi of the Central Kalahari Game Reserve - with access to their own Portable Rainwater Harvesters (PRHs). The four installed phase 1 PRH devices are now accessible to 60% of the resident CKGR population (three out of the five villages) Under the long-term average annual rainfall conditions, these four devices can collectively harvest around 8400 litres per year, providing much-needed supplementation to water supplies trucked in each month by the District Councils. Potable (non-saline) fossil ground water supplies in the CKGR are notoriously unreliable, expensive to develop, and difficult to maintain. It is also extremely expensive to transport water in each month to these villages by truck - the most remote of the communities being 140km, by sandy 4X4 track, from the nearest developed settlement! Watch the video's below (8th April 2019), showing some of the community members extract water from a 2,500 litre capacity PRH device set up at Mothomelo: Over 200 litres were extracted after a single brief rainshower, which fell whilst we were still setting it up earlier the same day. In phase 2 - planned for later this year - another installed 23 units will have the capability of meeting the drinking needs of the entire CKGR human population (est. at 306), without having to rely on any other artificial supplies. Funding support for phase 2 is still needed! Thanks to Mike McCune and Karen Kaye Smith-McCune of San Francisco, for their donation towards the PRH initiative and for helping to make this important exercise possible! Last week we installed another Portable Rainwater Harvester (PRH) for a remote community in Northwestern Botswana. As with other PRH units installed recently, the device will dramatically reduce the time and labour involved in fetching water from existing supply points, in their case an unreliable borehole. For this particular community, the PRH unit shown - under average annual rainfall conditions (450mm) - will yield around 10,000 litres of clean drinking water per year on an ongoing basis - at zero cost to the community and with no outside maintenance support required ever again! For this community it amounts to the equivalent of 700 litres of clean and easy-to-obtain drinking water per person per year, or 2 litres of clean drinking water per person per day. Whilst out in the area, we also initiated training of 8 selected community members in spoor surveying methodology, in preparation for our planned Community Wildlife Monitoring program, which will assist KWT, the communities and other stakeholders in better understanding wildlife population distributions and movement dynamics in Western Ngamiland, and in terms of cross border movements between Botswana and Nambia. Needless to say the superb tracking abilities of the Ju/hoansi San team members and their enthusiasm for protecting the wildlife populations of their envisaged (fencing-free) conservancy, all bodes well for the monitoring programme and their capacity to perform as custodians of their traditonal lands, which also will earn them additional income. Thanks also to Steve Huebsch of SC Projects in Maun for the discount on boots and other apparel for the trainees.

On the 31st of January, Sandi Albertson coordinated her third Kgotla (meeting) for the Boro1 Comunity, North of Maun. These engagements aimed to identify: talented art and craft producers (both young and old); individuals for mentorship and training of those interested in acquiring specific skills; and viabe products for further development. Now that the people and products have been identified, the intiative aims to develop the capacity of the Boro1 and other surrounding communities, to sustainably produce high quality and marketable products. So far truly amazing talent amongst the community has been revealed and there is great potential for income genertion from passing trade along the Sir Seretse Khama Road which Boro1 lies adjacvent to.

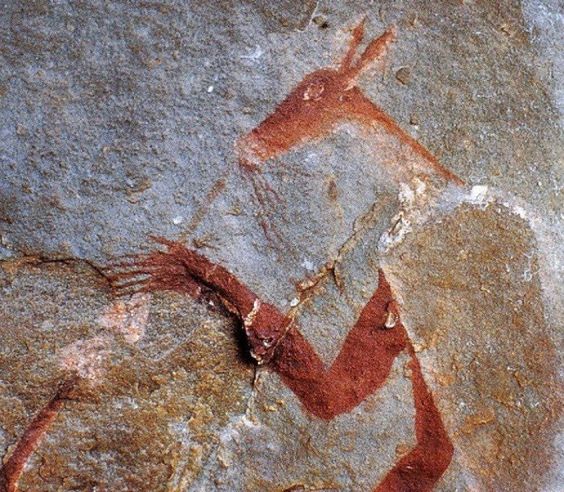

In December 2017, with the support of the Kalahari Peoples Fund, we initiated the recording of unique and endangered traditional knowledge at one community locality. Thanks to the support of Steve Stockhall and Robyn Currell of Earth Ark Photo Safaris, who kindly donated towards this cause in December 2018, our work on this has resumed and we are in the process of finalizing the first phase of the interview transcripts from 2017. A second phase is being planned for February, which will follow up on some fascinating cultural knowledge aspects. Amongst the aspects we are assessing and documenting include:

Traditional territories, place names and their meanings; historical movement patterns; personal histories and life experiences; use of medicial plants not yet documented (e.g. cures for snakebite, arrow poison antidotes); other unique skills and phenomena etc. As follows is an intriguing sample extract from one of the elders interviewed, concerning a first hand encounter with a group of San who reportedly had the ability to change their form into lions at will and reportedly also used it as a hunting method: "He said to the people who changed themselves into lions: "I know you really are people! Why did you change yourselves into lions?" And then they began to close their eyes and change back into human beings. They then came closer to the fireplace and they asked for tobacco." There are in fact several elders who have personal knowledge of the shapeshifting phenomenon, regard it as historically integral to their culture, and claim to have personally witnessed its manifestation on numerous occasions including in relatively recent times. This is an example of one of the more mysterious aspects we aim to document in more detail, as agreed and supported by the elders concerned. The San represent humankinds oldest and purest genetic lineage (it is at least 150,000 years old), and the skills and knowledge still posessed by the few surviving elders today are truly ancient and have been passed down largely unchanged over many thousands of years. It has now literally become a race against time to document these unique knowledge systems before the opportunity to do so disappears forever, which tragically will be in only a few years from now. Urgent funding support is needed to expand our knowledge recording efforts to include as many elders as possible, within the over 30 dialect groups comprising the San in Botswana, as well as other groups with unique traditional knowledge (e.g. Bakgalagadi). Our aim is to record unique and endangered traditional knowledge, at the request of those Communities that have expressed concerned about loss of knowledge and lack of inter-generational transfer. Of paramount importance is to uphold their exclusive intellectual property rights, safeguard sensitive information and disemminate information only in close consultation with the communities concerned and the elders in particular. We will also focus on getting the recorded materials back into the Communities to foster custodianship and transfer to the younger generations. Heritage Trail update: In November, Arthur and KWT community liaison officer Sefako Chumbo facilitated consultative meetings at 7 villages scattered across Western Ngamiland as part of the Heritage Trail project (see post below). Of the populations encompassed within the project area (see map in post), these villages are amongst the most remote and marginalized in terms of lack of livelihood opportunities and involvement in tourism. Our main aim, apart from gathering base-line data, was to assess opportunities for developing tourism facilities, products/activities and the required spatial linkages. This vast sandveld area currently sees virtually no tourist traffic, despite having excellent widerness landscape, wildlife and cultural attributes. In collaboration with our project parners, Botswana Predator Conservation Trust, we plan to finalize a feasibility study by February 2019, which will identify priority activites for the envisaged pilot 4X4 heritage trail, which will link up these remote communities and adjacent habitats with the self drive and mobile safari markets. A plentiful supply of "Monkey Oranges" ("Mogorogorwane" Strychnos cocculoides) from the Shaikarawe community provided our team with much needed refreshment against the scorching heat! Kagusi Wilderness Campsite update:

In December the Botswana Department of Tourism granted a tourism enteprise licence for the Kagusi Wilderness Campsite, a joint collaboration between Athur and Sandi Albertson and a remote Ju/hoansi San community in Western Ngamiland. Initiated in 2010, the project has faced many challenges, mostly delays associated with the administrative prerequisites to the tourism licensing application. As a unique low-impact cultural / wilderness experience, this low-volume tourism activity will generate much-needed income and other benefits for the community. It will also compliment the work of KWT in the area, which is aimed at assisting the communities to protect their ancestral lands, rehabilitate local migratory wildlife populations, conserve endangered cultural skills and knowledge, and secure livelihood income on an environmentally sustainable basis. In early October, we travelled down to GH11 - a remote Wildlife Management Area located west of the Central Kalahari Game Reserve - where we installed the first of 10 Portable Rainwater Harvester ("PRH") devices we've manufactured so far this year, from sponsorship received from the Comanis Foundation. The PRH device (our own invention) will provide vulnerable, water-stressed communities with an extremely useful adaptive coping mechanism, at a time when the effects of global climate change are already showing signs of accelerating. One of these devices can yield enough drinking water to sustain up to 11 people for a year, at annual rainfall as low as 350mm (typical drought condition). Its effectiveness lies in its ability to efficiently capture any amount of rainfall and protect it from contamination and evaporation - a critically important feature, considering that evaporative water loss in Botswana often exceeds 2000mm per year!

Amongst its mutiple benefits, the PRH will help the San and other similar communities by facilitating their access to useful natural habitats - situated away from the settlements - that are still unaffected by livestock overgrazing, as well as those areas that are naturally richer in supplies of wild plant food species. Such areas have become difficult to access due to the lack of surface water and the required travel distances, as compounded by the difficulty in transporting drinking water, which makes it extremely impractical to undertake effective gathering expeditions for effective plant food harvesting. Rural settlements and cattleposts - where water supplies are currently located - are characterised by widespread overgrazing by livestock and the depletion of most of the surrounding natural plant food resources on which the original occupants of these areas historically relied, thus compounding dependencies on foodstuffs sold in local shops, which are typically too pricey to be accessible to most residents and at any rate are extremely limited in variety and deficient in essential vitamins and minerals. By contrast, over 100 species of wild, drought-tolerant, plant food species are potentially available for use in natural Central Kalahari habitats, often with nutritional qualities far exceeding that of processed foodstuffs. The PRH therefore has the potential to impact positively on the food security of many struggling and malnourished rural dwellers, in particular the San. It also has good potential for promoting the preservation of traditional knowledge and culture through skills transfer and as a water supply alternative for remote tourism operations in dryland areas where potable ground water extraction is prohibitively expensive and impractical. The primary advantage however lies simply in improving the overall reliability and supply of clean drinking water for people - wherever they may live - and in freeing water-stressed communities from their current over-dependence on centralised water supply points that are costly to maintain and ultimately unsustainable due to the lack of recharge taking place in the deep fossil underground water acquifers they extract from. The PRH essentially dramatically reduces the daily personal health risks and energy expenditure involved in accessing conventional, centralised water supplies as users can install it at optimal and conventient locations (e.g. right where they live) and it empowers users to independently manage - by way of a single device - their own drinking water provision, on an ongoing basis and from source through to supply. |